Saint Olof’s church in Jomala is centrally located in Åland, immediately adjacent to the largest Iron Age graveyard. It was erected in the middle of Jomala plain, which is abundant in limestone, but without direct contact with the sea.

Yet the church tower serves as a characteristic landmark for seafarers from afar. It has generally been seen as one of the oldest stone churches in entire Finland. In ground plan, proportions, and in the use of stone sculptures in the decorative program, it radically differs from all other Åland churches.

Exterior from the southwest.

The exterior

Jomala church, detail of the east wall of the tower.

Already on the exterior Jomala church reveals a complicated and multifaceted building history with a number of secondary interferences. Traces can be seen of both demolitions and later additions. The church is built of selected small stones in local red granite, (rapakivi*) mixed in with plenty of local Ordovician* limestone. The limestone is to be found in the walls, in the corner chains, and as decorative framework in the west portal of the tower.

The high west tower has shingle covered “shoulders” cut off against the nave. On the eastern wall of the nave the original roof angle of the nave can be traced. It is evident that the original roof was both taller and steeper, and that the shoulders of the tower were adjusted to it. The wide body of the building, or the transept in a north-south direction, which has been added to the nave in the east, today has the same roof height as the nave after the demolition. Uniform stepped cornices underline the likeness. Nor does the masonry of the transept differ all that much from the original walls of the nave. But the framing of the portals towards the north and the south indicate the beginning of the 19th century. Also the eastern addition, the sacristy, with bricks in the upper part of the gable, stands out as a feature foreign to Åland church architecture.

The northern and southern facades of the nave show traces of walled-in portals in the south and the north, placed axially opposite each other in the western part of the nave. Large window openings have later been hewn through the northern and southern walls.

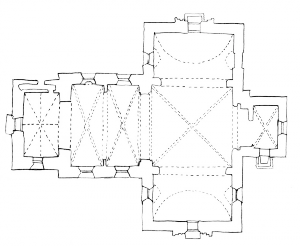

Ground plan.

The ground plan

Jomala Church has an unusual T-formed ground plan. A nave of 9,3 m x 10,9 m, where the width exceeds the length, is finished in the east with a transept oriented north south. The west tower is connected with the nave, and in the extension of the nave to the east the church ends up with a sacristy, with a separate entrance from the south. The ground plan is the result of the radical interference and building alterations made during the 19th century. The western portal of the tower and the portal in the southern transept form the main entrances to the church.

Interior towards the tower arch in the west.

The interior

Inside the church the various building stages can be clearly discerned. The changes of the 19th century with smooth and bare wall surfaces to the east are markedly different from the medieval parts of the original nave and the west tower. The medieval part of the church to the west gives a warmer impression, and fragments of high-class lime paintings can still be seen on the pointed arch of the tower, on the west gable, and on the north and south walls of the original nave. The arch of the tower rests on solid supports of limestone, covered with wide, profiled limestone slabs. A strangely placed human face sculptured in limestone remains in situ on the northern shelf of the vault. The face is sculpted in the corner of a horizontally placed slab of limestone. Yet rough chisel marks on the upper surface indicate that the position may be secondary – the lower surface is beautifully profiled and neatly edged. A rough broken surface on the corresponding limestone surface on an opposite southern slab indicates that there may have been a similar stone carving. The interior also shows traces of walled-in southern and northern portals. The uniformly cast vaults in both transept and nave show that they belong to the same secondary building stage which can further be seen in the attic of the nave. The demolition of the original vault and the lowering of the roof are very clear. In the process the walls of the nave were also leveled and with them the largest part of the large attic openings towards the north and the south. Only the roughly cast tower vault remained intact in the process.

The building history

The building history of Jomala church is not yet fully investigated. Archaeological excavations on the site revealed no traces of a possible older wooden church. But there were plenty of signs of ecclesiastic activity during the beginning of the 13th century, i.e. during the Romanesque period.

The ”Jomala lion”, and the human face, both in limestone, are the only examples of stone sculptures used in the architectural decoration of the Åland churches.

Limestone elements were conspicuous in the architecture: portals as well as windows were framed by limestone. But Jomala is also the only church in Åland where limestone sculptures have been part of the ornamental program. The Åland Museum today houses a limestone sculpture found in a closet in the church at the beginning of the 19th century: a lion head, with a human face in its mouth. The sculpture is Romanesque, that is, it belongs stylistically to the time before 1250, and it might have been suited as a gable ornament on the separate chancel torn down in the 19th century. The human face on the northern shelf of the tower arch is also Romanesque in style. The limestone sculptures and certain building details point to the possibility that the nave and the chancel might have been somewhat older than the west tower. We do not know exactly what this potential Romanesque church looked like. But we do know that it had an appearance totally different from the other Åland churches and from other contemporary churches in general.

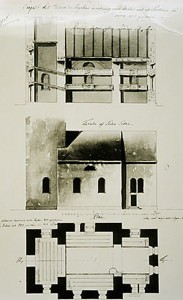

Alteration drawing from 1808.

The church was already considered too small in the 1600s. To deal with the problem an alteration plan was drawn in 1808 at the Royal Superintendent’s Office in Stockholm. The drawing, which was not realized, is still preserved. It provides valuable information concerning the church, indicating how it appeared before the great architectural changes in the 19th century. As a historical source, however, this drawing is problematic. In addition to the planned double galleries in nave and chancel it includes suggested changes around windows and portals. Yet it gives a trustworthy picture of the church, of what it must have looked like in the 1280s, with the west tower finished and the original chancel without an additional apse in the east.

We see a unique solution where tower and chancel together with the nave form a symmetrical and well-proportioned architectural body. The nave has unusual dimensions, with a width exceeding the length. It is flanked in the east by the chancel, with a straight eastern wall, and by the tower in the west. The chancel and tower have almost identical proportions, being also wider than they are long. In spite of the drawing the chancel was probably lower than the nave, and we know that the shoulders of the tower really formed a continuation of the roof of the nave.

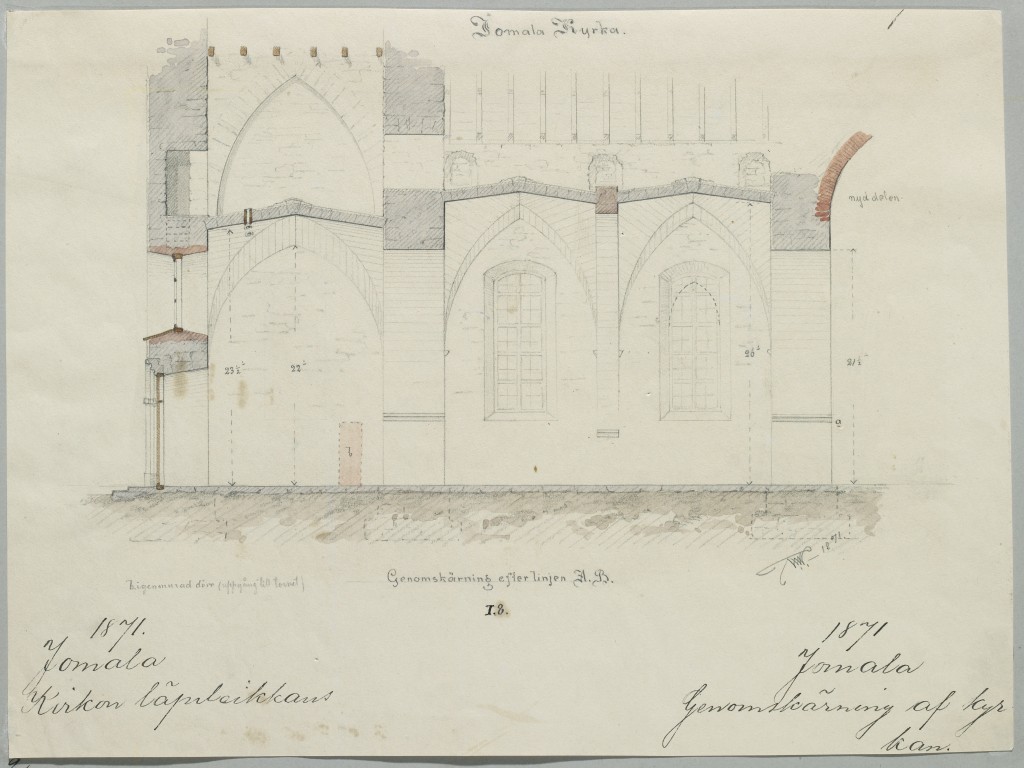

Longitudinal section, documentary drawing from 1871.

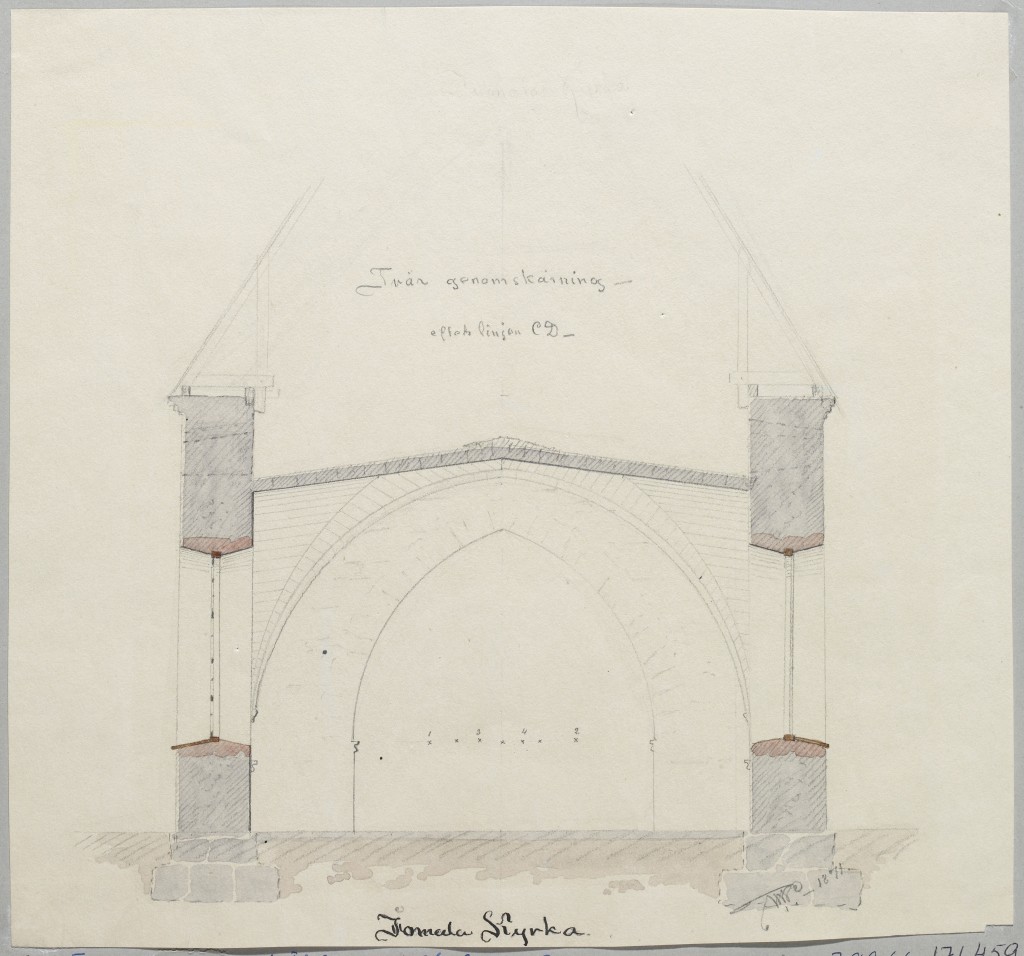

Transversal section, doumentary drawing from 1871.

Important details, not evident from the 1808 drawing, are well complemented in the documentary drawings made during the First Art Historical Expedition in 1871, conducted by the Finnish Antiquarian Society. The architect Woldemar Westling made his documentary drawings for the transversal section and for the longitudinal section of nave and tower in the last minute, at a stage when the vaults of the nave, the triumphal arch, and the attic of the nave were still intact. All of this was demolished in the 1880s.

We can see that the triumphal arch in the east repeats the same shape as the tower arch between tower and nave. The nave is divided into two wide and short bays. Two vaults cast in fieldstones with exceptionally wide spans, rest on low profiled brackets of limestone. Above the nave is shown an intact attic, with three large openings facing north. Because of the demolition of the vaults mentioned above, this attic is today severely damaged. Yet one can still see fragments of the preserved openings, also towards the south.

So far the connection between tower and nave remains unclear. A cavity from the westernmost roof truss of the nave is seen in the outer east wall of the tower, which indicates that the tower at this stage is part of the construction of the demolished roof. A couple of mortar samples do however suggest that the attic floor may have belonged to the original Romanesque stone church, from the beginning of the 13th century. More mortar samples should therefore be analyzed, especially from the socle level of the nave. Nor is the original function of the attic floor clear, but there were for instance corresponding defense attics in Romanesque churches in Öland, Sweden. It is also possible that the space above the vaults was used for fireproof storage.

Reconstruction of the interior towards the chancel of Jomala church. The wall paintings on the triumphal arch are pure fantasy, but they they correspond roughly with the wall paintings on the west gable of the nave, and they give an idea of the original coloring of the church.

The documentary drawings from 1871, by Woldemar Westling, facilitate a reconstruction of the church interior Towards the chancel in the east and towards the tower in the west, identical high-pointed arches limited the nave, both resting on limestone support. The main entrance of the church, facing south, was located in the western side of the nave, axially opposite the northern portal of the church. A priest door led directly to the low chancel, with a straight east wall. The chancel had plenty of light openings, towards the east a so-called Trinity window with three narrow windows placed tightly together, and two coupled windows towards the south.The west tower was erected in the 1280s, contemporary with the painting program on the walls. The Crucifix from the end of the 13th century was probably hanging in the Triumphal arch, resting on a transversal beam. Two sculptures are placed on each sidealtar flanking the chancel, to the north we see Mary, and to the south a sculpture representing Saint Olav of Norway, the patron saint of the church.

Up to the 1830s the medieval church seems to have been preserved more or less intact. To prepare space for “another nine farmers” in the 17th century, the two side altars at the chancel were torn down. As far as window openings and portals are concerned, the preserved drawing from 1808 includes planned changes, in Empire style. In this case a drawing from the 1840s gives a more accurate picture of the original south façade.

Considerable changes were initiated by the Imperial Intendent’s Office in Helsinki in 1824, to be finished after many sorrows in 1844. The broad transept substituted the demolished original chancel with a sacristy in the east. By mistake the transept became too low. To form a uniform silhouette, the roof above the nave was lowered as late as 1884. That did not only destroy the defense floor, but the magnificent fieldstone vaults of the nave were also demolished, together with the triumphal arch between nave and transept.

The wall paintings

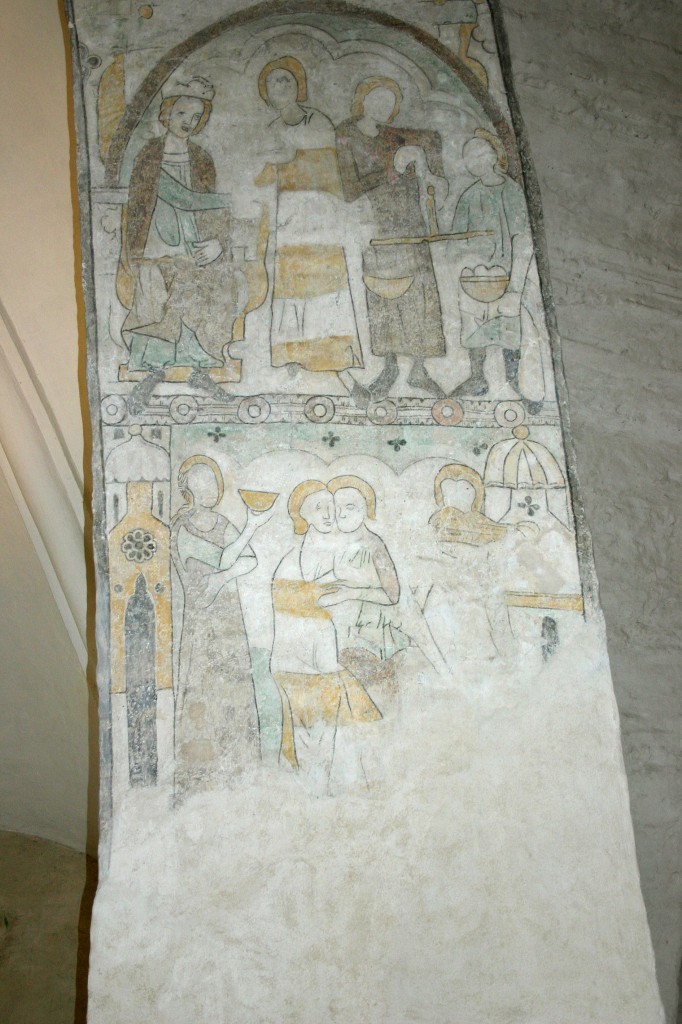

The interior of Jomala Church was originally covered by early Gothic wall paintings from the 1280s. These paintings were strongly polychrome, in yellow, blue, green and red. At least three different pictorial sequences on top of each other were separated by ornamental friezes. The actual sequence of the events described can be discerned only in the tower arch and in the western gable of the nave.

Wall paintings on the tower arch, from the 1280s.

The tower arch probably represents scenes of a courtly nature from the biblical parable of the prodigal son. The main figure is dressed in a tunica striped in white and yellow. Uppermost to the south the enthroned and crowned father distributes his legacy; uppermost to the north the son proudly rides out with a falcon, a hound and a splendid retinue in order to conquer the world as a knight. Down towards the south we can see a fragmentary scene from a brothel where the son is enjoying himself, while the damaged scene down towards the north probably represents his homecoming.

The western gable (see interior above) towards the nave represents the Day of Judgment, with the Throne of Grace (the crucified son in his father’s arms) as the executing judge. Down to the north the damned walk in towards the gap of hell, while the blessed walk southwards towards the gates of heaven. On the northern wall of the nave a wheel of fortune can be fragmentarily seen, marked with the four ages of man (childhood, youth, manhood, old age). Fragments of a Romanesque ornamental frieze, sporadically preserved along the walls of the nave, show that the walls here too have been covered by polychrome mural paintings in several friezes on top of each other. This probably also goes for the vaults in the nave and the chancel.

Inventory

The crucifix.

Jomala still has a rich treasure of sculpture preserved in the church. The first to be noted is the crucifix to the left of the altar. It is probably from the latter half of the 13th century, imported from Gotland. In the 14th century it was subjected to some modernizations, when for example the clusters of blood were added, to express the new philosophy of suffering of the time. The cross itself has unfortunately been lost.

.

Saint Anne

A Mary sculpture from the early 14th century, north of the tower arch facing the nave, has later been altered to Saint Anna. Another sculpture of Mary with the infant Christ standing in her arms (south of the tower arch), is of unknown date. Fragments of the late medieval triptych (from the 15th century), representing the Deposition of Christ from the cross, are found on the southern and northern walls of the tower. All sculptures were originally strongly colored and gilded.

The medieval font of the church and a stained glass window from 1968.

Even the medieval font, of Gotland limestone from the middle of the 13th century, has been richly painted in different colors. Today all traces of color are missing. On the wall a detail of the “Deposition from the Cross” a fragment from the medieval altarpiece.

During archaeological excavations in 1961 a large number of glass splinters were found. They date from the 1280s and are of Gotland origin. Probably all the windows were equipped with precious stained glass. A large number of coins were also found during the excavations. The great majority of these were from the end of the 13th century, but in the nave eighteen coins from the beginning and middle of the 13th century were found.

The modern stained glass window in the porch represents Saint Olof and was made by the American artist Thure Bengts, of Jomala origin. It was donated by Professor Bengts and unveiled in 1968.